The other day, I was looking to buy a jump rope I could travel with. After spending (wasting?) about 30 minutes going through jump ropes on Amazon caused by searching for “best MMA jump rope”, I paused to ask a highly relevant question: what in the world was wrong with me? Why did I need “the best” jump rope? The previous jump rope I owned came from who knows where and served me fine for a long, long time. The experience felt like living my own version of Aziz Ansari’s piece about trying to find the best toothbrush.

Last week, I had a great lunch conversation with my friend Lexi Lewtan (currently building AngelList’s A-List job platform) about something similar she was noticing in the recruiting industry. Companies all wanted to recruit “the best” iOS engineer or designer for their company even though that bar is subjective based on what that company is building. No one, not even early stage startups, wanted to settle for hiring an average engineer, even if that meant huge cost savings and would get the job done perfectly well.

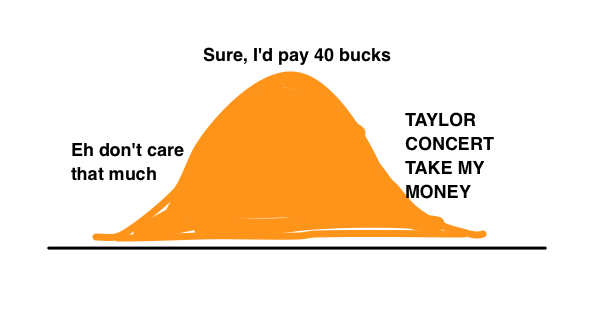

We’re taught in economics, entrepreneurship, and statistics classes to assume that most things lie on a normally distributed curve. This is especially true about demand – at some prices, I’d like to buy a “widget” while at higher prices, I wouldn’t.

Anecdotally, it seems that this assumption is falling apart. Alex Danco wrote a great post about this called Taylor Swift, iOS, and the Access Economy: Why the Normal Distribution is Vanishing so I won’t rehash that here but definitely go give it a read. Seriously, I’ll wait.

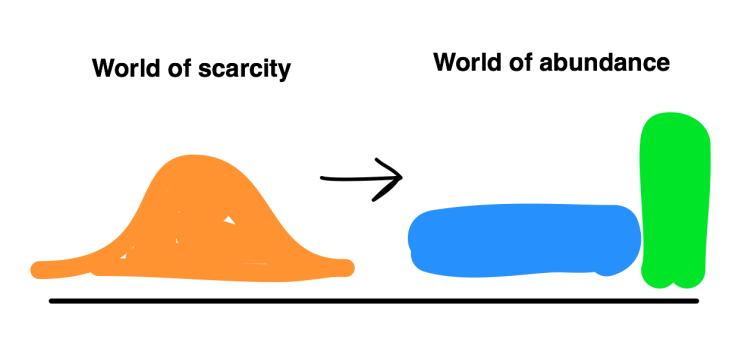

Essentially, the post boils down to the world moving from one of scarcity to one of abundance and that leading to a breakdown of the normal distribution curve:

To build on Alex’s great post, I think we’re moving to an even greater dichotomy. We’re going to live in a world where companies AND people are either luxuries OR commodities. This trend is showing up in industries as varied as cosmetics, labor, food, and much more. Let’s start with some definitions; what’s the difference between a commodity or a luxury in this context?

Commodity: A product or service for which I’m brand agnostic and highly price sensitive, usually because I believe there is no major difference in quality between brands OR it’s just something I don’t really care about. Examples (for me): gas stations, drug stores, bottled water, socks, paper towels…the list goes on.

Luxury/Premium/Prestige: These are products or services for which I’m highly brand/review sensitive and minimally price sensitive. Things in this category for me include coffee, beer, shoes, cell phone, computer, chocolate, and many, many more. The luxury/premium/prestige category is the one where you would search for “the best” on Google or Amazon.

One key thing to remember is that the determination of a commodity or a luxury is an individual thing – for example, some people think all beer tastes the same and treat it as a commodity. I think differently and am willing to pay a huge premium for beer that I think tastes better, uses more valuable/rare ingredients, and has a better story behind its creation.

The easiest way to test whether something is a luxury or commodity for you is to imagine the price of product X increased by 10%. Would you still buy it or would you switch brands? For example, for most people, if a cup of Starbucks coffee increased from $2.50 to $2.75, they wouldn’t think twice about continuing to buy Starbucks. Similarly, if the price of a 15 inch Macbook Pro went up from $1,999 to $2,299, most Macbook Pro customers would still buy it (although probably with some complaining).

Let’s look at how the luxury vs commodity trend is affecting three very different industries:

Cosmetics

I’ve been spending much of my time studying the cosmetics industry because of my work at The Estee Lauder Companies. Since my role is to look externally, I’ve been watching how companies position themselves and how they’re adapting to this new luxury-commodity dichotomy.

One of the biggest moves last year in cosmetics was P&G divesting a huge chunk of their beauty business in a $12.5 billion sale to Coty. One of the striking things about that transaction is that P&G chose to hang on to its most prestige skincare brand – SKII. In another example, Unilever, a huge personal care company that traditionally stays in the mass-market world with brands like Axe, Dove, and Degree, bought 4 prestige beauty companies in 2015 and they’re on track to acquire more in the future.

“Prestige is growing much faster than the mass market”

-Alan Jope, President of Personal Care, Unilever

For beauty brands, there isn’t much room left in the middle – either you’re making commodities that are competing on price (in which case, your gameplan should be to cut costs as much as humanly possible and sell at grocery stores and drug stores) or you’re competing on uniqueness and luxury, in which case you need some product, marketing, or service elements that stands out.

Labor

If you think about labor in a “prestige” vs “mass-market” manner, you see a similar thing happening. Companies look to hire world class full-time employees for a select few key positions and for everyone else, they’re OK working with outside firms or freelancers. This makes sense from their perspective: why invest additional overhead for average talent when you can replace it easily with the next person who walks in the door?

This trend is part of the reason we’ve seen marketplaces for unskilled labor pop up everywhere over the past few years – not just Uber, but also Fancy Hands, Handy, Wonder, and much more. The people working for these companies are all contractors, which is a much cheaper arrangement for companies than hiring full-time, allows flexibility for workers, and allows companies to adapt dynamically to demand in the marketplace (Uber’s surge pricing is the best known example of this).

On the other side of the unskilled labor marketplaces, highly skilled individuals in certain industries have seen their salaries climb higher and higher as firms bid for their talent. This can be seen on a wide scale by looking at software developer salaries or the long-term rise in CEO pay at Fortune 500 companies. As much as it would be fun to complain that these pay issues are all about corporate greed (which is certainly a factor for the CEO pay issue), at the end of the day, it’s really about companies bidding against each other for talent that they want to acquire or keep at all costs – aka the luxury talent.

Food & Beverage

Believe it or not, there was a time when coffee was a commodity item. For those of us who’ve grown up in the era of the $5+ latte, the commodity coffee era is a difficult world to imagine. I assure you, however, a world in which coffee consisted of hardly drinkable sludge that cost $0.50 was a very real place.

The late 80s and early 90s featured the rise of a company called Starbucks. You may have heard of them. The key distinctive trait of Starbucks was taking a commodity item that no one thought much about and elevating it to a level no other coffee retailer had imagined or done on such a large scale.

What does the word elevating mean? In this context, elevating coffee meant Starbucks started with higher quality beans than any of their existing competitors (luxury), roasted them with a more precise science than their competitors (luxury), integrated the story of Italy, espresso bars, and the Third Place (luxury), and included an ethical component (luxury). Compare that to a gas station that would pour some black sludge in a styrofoam cup and sell it to you for $0.50 (commodity). All of these elements factor into giving Starbucks the cache to sell a commodity product as an affordable luxury for almost 10x what their competitors were selling at. Howard Shultz (the man behind Starbucks) tells the full story behind the commodity to luxury rise in detail in his book Pour Your Heart Into It: How Starbucks Built a Company One Cup at a Time.

Today, the rest of the food & beverage industry is doing its best to try to break out of the world of commodity items. Whether they do or not remains to be seen but the tide has turned in luxury’s favor as more and more people are paying attention to the ingredients in their food. This creates an opportunity for brands to elevate (there’s that word again) healthy ingredients, the lack of preservatives, ethical sourcing, freshness, or dozens of other desirable food characteristics.

Commodity vs Luxury: The Way Forward

The main, short-term outcome of this commodity vs luxury transition is that companies are going to be forced to make decisions about how to invest in their futures. My guess is that more companies are going to invest in building brands that are luxuries. Why? Because a luxury’s key differentiator is uniqueness – which could come from a unique ingredient, a novel process, or a fascinating background story – any and all of which can be sustainable competitive advantages.

Building a commodity business seems to me as an outsider to be a lot more difficult. Commodity businesses would be competing mainly on price which makes it easy to imagine commodity businesses becoming a race to the bottom with margins getting slimmer and slimmer until there are no profits to be made. Commodity businesses survive on high volumes and while of course there will always be a (huge) market for them, I think we’re moving to a world where people will buy a higher percentage of products at a premium that last longer, work better, and are more unique – which by necessity means purchase volume will go down. This trend could also be tied to growing income inequality – fewer people in the middle class – but that requires more research to figure out.

Something I haven’t mentioned anywhere else in this post but runs in the background of all these trends is technology. Technology, especially data but also includes manufacturing tech like 3D printing, is giving companies the ability to create customized and personalized products in almost any industry – which is certainly one way to create a premium product. When a company has created a customized product for you and owns the data to continue improving that product, it becomes a premium experience with a competitive advantage. That’s a tough combination to beat.

Thanks to Lexi Lewtan, Brett Martin, and Josh Dodds for their feedback on early versions of this blog post.

What an interesting, thoughtful article. It seems that every company tries to build “value” into their products by making it less of a commodity. “Commodity” is kind of a mindset to sell against in today’s economy. It’s interesting that being a luxury brand has negative connotations though. It goes against a lot of the common marketplace values to consider themselves buying luxury. What a balance it is to normalize luxury but still keeping the exclusivity that it sells.

Great article. Great perspective